Introduction

It is a hot, sunny in the Brazilian summer. We are in the Vale do Ribeira region in the state of São Paulo, in the city of Barra do Turvo, in the quilombo community of Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca. Quilombos are communities that were founded by escaped slaves.[2] Around 20 of us are trying to install a bamboo tower. The material was previously treated in a collective workshop to make it even more resistant to weather and time. On the top of the tower is a router, one of the nodes of a community network being collectively built in an area without internet connectivity.

The process of erecting the tower requires collaboration: we divide into scattered groups, pulling the ropes that will raise the tower in a coordinated way. In the end, there’s a shared joy of achievement. And here we are with a tower made of a local material. It’s standing, able to resist wear and tear for many years because of the technology used to treat this wood; and it can keep carrying digital technology—the router on top has been updated to operate in a collaborative network protocol. Different people, knowledge, background and materials (bamboo, wires, antennas) came together, and now this node is ready to connect with other ones covering the territory.

Our group of women came from São Paulo, Brazil’s biggest city. In spite of the high temperature and the physical effort to raise the tower, we accept the hot coffees offered to us. With each sip, we, the women from our project’s team, try to become familiar faces, not just people from the city. Trust and affection is a fundamental aspect of socio-technical networks, such as community networks.

The blue sky and preserved natural hilly landscape contrasts with the daily challenges the members of the quilombo community (quilombolas) face to keep their lands, rights, ways of living, knowledge and technologies. In the second half of the twentieth century, so-called ‘development’ projects, such as the construction of roads, dams, and mining, arrived in the region. At the same time, the Vale do Ribeira has three national parks and many traditional communities’ lands. It is not difficult to imagine how the region’s history has been affected by land conflicts and struggles for better living conditions. However, the region also carries memories of resistance:

Vale do Ribeira, located in the extreme south of the state of São Paulo, is the largest area of continuous Atlantic Forest remnants in Brazil. The presence of countless traditional communities made it possible to conserve these areas. In the region, there are 24 indigenous Guarani villages, 66 quilombola communities and 7,037 family farming establishments that involve traditional peasants (the ‘caipiras’), traditional fishermen (‘caiçaras’), and migrants from the Brazilian metropolises (generally, children of farming parents who were expelled from the land in the past and pushed into urban areas and who are now returning to rural activity).[3]

The Vale do Ribeira region comprises 25 cities, including Barra do Turvo, where there are seven quilombos recognised by the Brazilian authorities.[4] One of them is the quilombo Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca, where our community network emerged through an action-research project developed between 2019 and 2021. The network was founded by a group composed exclusively of women[5] while conducting a participatory research process.[6] They were supported by the Feminist Internet Research Network (FIRN) through grants and constant feedback on our reflections and by providing exchanges with other researchers from the Global South.

The project envisages the implementation of a Wi-Fi community network in quilombo Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca by actively encouraging the involvement of the entire region in multiple workshops and knowledge exchanges about networks; feminist infrastructures; popular education; agroecology; gender and race relations; traditional and digital technologies; and technology and communication autonomy. The project also aims to build knowledge in these fields, based on reflections that have emerged from this localised experience and the encounters it promoted.

It is worth sharing that the definitions of community networks can vary a lot depending on the context in which they are implemented. However, a common element is the search for autonomy—even if that is a relative concept—from the models of connection and communication established by the profit-oriented big telecommunication companies. Here, we understand community networks as a solution to reduce the lack of connectivity[7] in rural areas, urban peripheries and other places (in Brazil and around the world) that are currently not connected because of a commercial approach to connectivity. This can be achieved through the collective installation of a local-level infrastructure and shared management of the technical and human aspects of a network.

Recently, community networks have been argued to be an alternative to the search for greater autonomy[8] in relation to communication and connectivity and to promote local social interactions—in distinct territories—through digital infrastructures.[9] As a result, the debate on community networks has been gaining new perspectives, going beyond the field of connectivity solutions for places and populations without internet access. The idea has become linked to other political agendas, including, as in this case, the intersectional feminist perspective.[10] Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw conceptualised intersectionality to denote the various ways in which race and gender interact to shape the multiple dimensions of black women’s employment experiences. Although her theory has aroused controversy, Crenshaw helped to make visible some of the dynamics of structural intersectionality and pointed out that people and groups experience the overlapping of discriminatory systems. She also pointed out the limits in identity politics, affirming that its problem ‘is not that it fails to transcend difference, as some critics charge, but rather the opposite—that it frequently conflates or ignores intra group differences.’ The author argues that the experience of black women cannot be captured only from the perspective of race, nor only from the perspective of gender, without incurring an erasure. Following the intersectional perspective, several feminist researches have pointed out the need to consider the combination of the multiple differences, such as those of class, race, ethnicity, age, and gender, which are part of women and specific social groups and should not be reduced to just one lens. For more information, see this report and the fields of feminist infrastructure and popular education, all of which seek to make the collective process welcoming to different groups and bodies, especially different women.

As researchers guided by these perspectives, we were committed to breaking hierarchies as much as possible among researchers, technicians, and the local community, as well as to escaping from pretensions of research neutrality or schemes that hierarchise the multiple subjects and knowledge.[11] We were a group of mostly white women from the biggest city in Brazil, supported by an international research network, who went to a rural area with a mostly black population. As such, we were aware that our position was not neutral, particularly with regards to geography and race. What’s more, we understand that the awareness of privileges and power asymmetries demands a change of attitude that goes beyond simply declaring them in the papers that emerge from our research and trying to adopt reflexivity as a political practice.[12]

Similarly, thinking about the technologies we bring to this project from experiences in the field and our activism, we want to avoid reproducing the notions that only experts and technicians have the best solutions to problems in communities or that digital technologies and internet connectivity can bring magical solutions to local and complex problems. Such perspectives often assume that communities facing inequalities and discrimination need definitive ‘magical’ top-down solutions, which can result in some social-technological choices being presented as universal, which is detrimental to extant experiences, local knowledge and multiple forms of communication and bonding.[13] Even with the best intentions, a project that comes to a community seeking instant solutions with ready-made set ups runs the risk of disregarding local knowledge. Community members, for example, will have great advice for where to put the antennas and where to have the best line-of-sight. They also have local communication strategies and their own communicators with interesting propositions for the local needs.

If the project comes with a ‘ready-to-use’ approach, the space for collective building is suppressed. Communities have their own past experiences of using forms of communication. They are the ones with knowledge of their territory and its history, their achievements and challenges. Without the collective building of the process, chances that the community members will see community network builders as service providers are higher, which could result in them not actually embracing the community network for themselves. In addition, if the project only or mainly addresses adult men and disregards all other perspectives and wishes, that will result in a layer of exclusion, even if your project aims to connect people in a collective, inclusive and meaningful way.

But what are the challenges when translating all these commitments and wishes into building infrastructure and digital networks while doing participatory research? Over the course of two years, we have realised that social interactions with autonomous infrastructure and networks are embedded by discussions, conflicts and negotiations; similarly, so is researching. In this article, we want to share these reflections, focussing on the gendered and racial aspects of our journey. We hope to open our own experience to others and promote knowledge exchange around feminist practices, ethics, technologies and research.

More than reaching answers, this question has helped us to expand a set of reflections from the encounter between different ways of living and building knowledge and techniques. To some extent, these escape normative models in the field of digital technologies—such as the overrepresentation of white males[14] in this field[15] and the processes of concentration of power on the internet[16]—but simultaneously interact with ‘unequal parts of privilege and oppression that all positions contain.’[17]

First Connections

We were introduced to the residents of quilombo Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca by partners from the Brazilian feminist organisation SOF (Sempre Viva Organização Feminista in Portuguese). Since 2015, SOF has been working with farmer women in the region through a feminist and agroecological perspective that is based on an understanding of economics centred around the reproduction of all the resources necessary for life and takes food production and consumption as a starting point in seeking the democratisation of all power relations involved in social reproduction.[18] SOF has been working with the local Agroecological Network of Women Farmers (RAMA), which is composed by groups of women from eight communities[19] in Barra do Turvo.[20] The proposal of the community network in this territory therefore begins with SOF’s and RAMA’s wish to contribute to and help facilitate the sale of organic products through the women farmers of the solidarity economy and agroecology networks in Vale do Ribeira.

Through this partnership, our project arrived in the territory with a stated desire for a community network that was also endorsed by an active and respected feminist group working in areas related to the feminist economy, the solidarity economy, agroecology and food sovereignty. We also had a human network already in place through these groups. In addition, SOF is a feminist group engaged with techno-politics and FLOSS (Free/Libre and Open Source Software) discussions, especially those concerning the role technology plays in shaping agribusiness and monocultures and creating barriers for food sovereignty and agroecology. At the same time, SOF had been looking for ways in which technology can be an ally to a feminist and solidarity economy approach, which was synergetic with the feminist infrastructure perspective adopted in this action-research project.

In a dialogue process with RAMA leaderships and SOF partners, we considered that our methodology should include feminist practices of reflexivity[21] and prioritise collective activities and participatory processes, rather than individual data collection, such as interviews or surveys. We agreed, therefore, that we would always do a preparatory stage prior to each field visit. This would be a period of immersed workshops[22] in the community, as well as a reflection on the immersion on our return from each visit, which would inform the preparation for the next visit and so on. Between the beginning of the project and March 2020, we followed this methodology and were in quilombo Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca five times, where we spent between three and five days during each visit performing immersive processes[23] of knowledge sharing. Due to the health crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic, we could not visit the community for many months and managed to go once again in January 2021, completing six visits in total. [24]

Women’s Participation

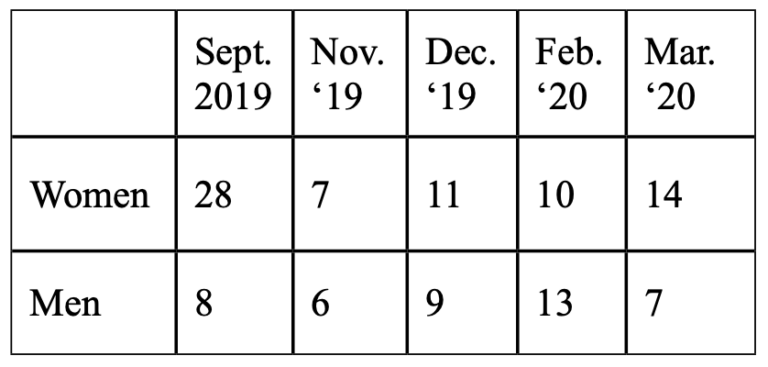

In other to make this process welcoming for different people, we approached the task from two directions: creating an experience that is both welcoming to women, which, at the same time, brings the feminist perspective into mixed groups involving all those in the community who want to participate. The following table summarises the participation of women and men in the immersions:

We tried to keep to our commitment to a balance between women and men among the groups mobilised through the immersions. However, this was not always possible for several reasons that we discussed with the people of the community through semi-structured interviews focussing on their evaluation of the process.[25] What was most pointed out by community members was the high amount of migration by young women (between 15 and 25 years old) from the territory, who left in search of work and more available opportunities in nearby cities that provided a greater demand for domestic work. They also leave the countryside for the city to study and/or to discover what is available to them outside their community.

Among those who stay behind, women tend to have more responsibilities in their homes with care and housework. In some cases, there are also gender stigmas—parents and husbands do not like women being out of the house and with people they do not know. This was indicative that, as in other spheres of social life, we were faced with unequal gender roles and other forms of discrimination that were present even in communities.[26] It is important to highlight, however, that more than arrive at an ironclad process or final result, we were looking to build safe and welcoming processes and spaces for different people. This avoided the naturalisation of inequality by being active when differences— instead of being respected and valued—are mobilised to produce discrimination and remove certain social groups from the place of technologies and knowledge producers.

Keeping in mind that being a feminist is a constant search for more balanced relationships and ethical practices (rather than a physical condition or a permanent state), we tried some specific actions to face the challenges of involving women and seeking gender balance. These included:

- Performing the immersions at a time compatible with the school schedule and welcoming children so that the people responsible for their care could also be present.

- Offering collective meals during meetings so that families’ food preparation would not clash with our workshops (and instead generate an income for the women in the community, who could provide their organic products and services to our project).

- Prioritising being a group of women facilitating the project, hoping that our bodies could help break any possible idea that the digital infrastructure and community networks might be an exclusively male activity.

- Adopting what we call the ‘coffee’ method. This involved taking the time to go from house to house in the community on the day we arrive, so that everyone had the opportunity to know us better. We spoke to the women leaders and ensured that everyone was invited to join us.

- Arriving in the territory through the partnership with SOF and the women of RAMA, which helped us decide the starting point and future directions of the community network with the group of women from the outset. By linking with SOF, these women were always involved in decision-making processes—even though they were not all present in every socio-technical workshop. Through the project, they assume the position of guardians of their community network by knowing where all the antennas are installed and where the signal of each antenna reaches. They are also the ones responsible for sharing the password of the network with families and preventing outlanders from going there just to use their internet.

Although this process didn’t guarantee the female majority we were hoping for, these actions seemed to work to some extent as we managed to keep the balance between women and men more equal than in other processes of community network installations we previously did in Brazil. We also experienced rewarding developments: almost immediately after we had connected the mesh network with an internet link, we received so much positive feedback from the community and could re-establish more robust communications with them. Women from their forties upwards—who were used to travelling to the surrounding highway to fish 3G or 4G signal to be able to do their economic activities related to agriculture (such as receiving the orders and the specifics of the delivery process)—could now do that in the comfort of their homes. In addition, internet connectivity has enabled women from RAMA to participate in online political events and webinars regarding the protection of their way of living and the nature that surrounds them.

And to overcome the obstacles, it was necessary to reconcile aspects of preparing the immersive processes with an ability to stay open to the unexpected and to what emerges from the encounter with the community members when we adopt a process of collective learning. In other words, we had to keep our listening and plans open to unforeseen developments, which are only revealed in the territory when diverse people are gathered. The barriers here lead us to an important reflection on the combination and balance between the importance of preparation and the ability to keep dealing with emerging issues while seeking to break with normative practices.

Race and Whiteness

Another important aspect of our process is considering intersectionality and not erasing the differences between women. Here, it seems crucial to highlight that ‘women’ or ‘community’ must not become shortcuts to ignoring the differences between women, especially with regards to race, ethnicity and class. Different feminist authors[27] have pointed out the need to question universalisation, which operated historically with the concealment and naturalisation of inequalities, including the homogenisation of women by erasing the combination of multiple forms of discrimination.

Once we arrived in Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca’s territory, we were asked about how we felt about being a group composed mostly of white women who had travelled from the city to the quilombo, which has a predominantly black population. This questioning was initially raised by the one black woman in our original group, which brought a concrete example of how often the ones who occupy the position seen as ‘universal’ naturalise that position, thus imposing a burden on the ‘not-universal’ social groups to speak up and break the silence. In this case, that was Daiane dos Santos Araújo in our small team.

Seeking to avoid perpetuating this situation, our group used this questioning and awareness raising to rethink how the issue of race should be addressed in our project, recognising the need to think more in depth about race and its different layers to lead to action. At this point, we separate what we adopted so far in this article to bring these reflections from two different places. On one hand, Daiane dos Santos Araújo built a reflection on race relations from a condition of alterity in our group and in many spaces of free technologies in Brazil. On the other hand, white women in our group also needed to recognise themselves as racialised in order to break the silence and act in the face of the privileges on which their race is structured. Discussions about whiteness were fundamental to achieving this awareness.

In her reflection on race, Daiane pointed out that, generally, the places that receive proposals for community networks in Brazil are racialised territories, such as quilombos, indigenous communities and urban peripheries. The construction of community networks is tied to the technological formation and knowledge that already exists in these territories. But today, the fields of production of digital technologies today mostly consist of white males. This is true not only true in terms of numbers; the whole thought process of digital technologies and their techniques come from Eurocentric and American perspectives. The demand for representation is a current issue, which had already been present in feminist research on digital gender gaps.

But we can also go further. When Djamila Ribeiro engages with literature from black women, she points out the importance of breaking with the naturalisation of whiteness, which is often seen as universal or neutral. This is also an objective in ongoing activist initiatives in Brazil, such as PretaLab,[28] which seeks to encourage and support the experience of black and indigenous women in technologies.

Moving from these reflections to the field of feminist infrastructures and community networks, there is a possible approximation in the sense of recognising the importance of representation but also of building a strong proposal to go further. In other words, having more social groups and diverse bodies in the design of autonomous networks is not just a matter of representation. It is also a decisive factor in promoting alliances that could be able to challenge naturalised and non-verbalised choices and the reproduction of norms and discriminations in the fields of network infrastructures and digital technologies. Bringing these perspectives to these particular fields highlights that the operation of a community network implies relationships between different people and social groups that will carry different perspectives, interests, needs. Given the existence of inequalities, not everyone will be impacted in the same way by socio-technical systems.

However, discussions about race are not yet seen as central to many projects on community networks. This silence on such a latent issue in this field may represent an echo of structural racism in Brazil. Initiatives, spaces and choices thought up by white men and women are loaded with assumptions and privilege baggage. However, the perception of whiteness as a universal condition means that destabilising assumptions and dealing with structural racism is not part of their lives, which could also be reflected in their projects, even in a country like Brazil, where more than half the population is black and where racism is such a historical and pressing issue. Daiane indicated this scenario as one of the key factors that made her rethink her involvement with community networks before we started this action-research project.

Furthermore, Daiane dos Santos Araújo indicates that being in the quilombo—a territory associated symbolically and historically with the black resistance in Brazil—made her reflect and want to remain acting in the community networks field. She views them as initiatives that can empower social justice processes since they are permeated by inconclusive and disputed processes. According to Daiane, the willingness to act in the construction of an egalitarian society presupposes reviewing ourselves constantly, which makes it possible to interfere, decide, compare and break through. And that indicates the need to transform our human and digital connections in a way that is welcoming to people who are not white.

If, like Daiane, we think that many black people can feel silenced and distanced from spaces of interaction with digital infrastructures and technologies in Brazil, how collective can the installation and management of autonomous and community networks actually be? And why aren’t white people thinking about how to challenge racism from their own position?

All of this caused the white women involved in this project to mobilise the concept of whiteness[29] as a fundamental pillar of our process. As a mostly white group, it was necessary to understand the position occupied by white women, considering that subjects who occupy it are systematically privileged with regards to access to material and symbolic resources. They are also part of a process initiated by colonialism and imperialism, which is still sustained and preserved. We believe that reflections on whiteness can and should be mobilised to challenge a general perception among white people that the only people belonging to a race are non-whites. This concept pointed us to the need for white people to raise awareness of their race more in order to promote changes in their micro positions of power and activity. And what’s more, to act in the general framework to engage with the structural change of cultural values so that whiteness, as a normative place of power, becomes white ethnic-racial identities where racism is not a prop that supports them.[30]

Feminist Infrastructure as an Evolving Field

From our previous experience in the field of feminist infrastructures,[31] we brought a perspective to this project that digital infrastructures are not based on binary or artificial separation between humans and machines. As we see it, infrastructures includes servers, networks, cables, antennas, software, hardware, as well as the use of the electromagnetic spectrum, protocols, and algorithm; this also includes the spaces, temporalities, priorities, relations between humans and machines, and agreements that can be (but not always) established, verbalised, visible and renegotiated when necessary.[32] Therefore, feminist infrastructures cannot be reduced to electronic materiality produced by women and non-binary people. The process is a central layer here, in which relationships are established locally and promote encounters that can lead to a commitment to rethinking through other perspectives—priorities, organisation of space and time, agreements, relationships between people and groups, and even between humans and machines.

In this journey with FIRN, SOF, RAMA and Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca members, we installed, together with the community, a bamboo tower, a wooden tower, and three nodes from a mesh network using LibreMesh,[33] installed on accessible CPE antennas and standard routers. So far, these collectively share the signal of a satellite connection between around fifteen families. In addition, there is a Raspberry Pi[34] with a feminist version of Pirate Box;[35] the Fuxico,[36] which performs the function of a small local server operating as a repository for documents and media exchanges, forums; and a local chat service.

So, even though the equipment and techniques were not the major focus of this research, we felt really satisfied that our process of popular education and feminist intersectional approach resulted in the women of RAMA owning the network. In our action research, we worked to build trust and a close relationship with the women from RAMA, and this co-construction led them to a position of guardians of the community network. This means that they all have a clear vision of the community network in their territory (they know where the antennas, routers and internet link are located and the equipment, such as a specific router, is called by the name of the household housing it). They also manage passwords for the community and recognise when and where maintenance is needed.

Ultimately, RAMA women were regularly informed and participated in the decision making through meetings, even though they were not always able to be present at the workshops and the implementation of the community network due to their daily and agricultural tasks. SOF also made sure their feedback constantly reached our group between the field trips. The women become the ones responsible for giving out passwords, knowing where the infrastructure is located, doing basic troubleshooting, and accurately informing us of bigger problems. The community also greatly appreciated that a women’s project brought the internet to the territory, which we believe helped to address some internal gender imbalances[37] as well.

Most importantly, they are able to use the community network to fulfil their own interests and needs in several different forms, including financially, politically, educationally and by fostering personal relations with the relatives and friends who no longer live in the territory. Among these different forms, we highlight the positive impact of digital communication on their sales process, political articulations, education and affective relations.

First, the communication made possible by the community network facilitates their production processes and sales because the community network helped expand their communications with each other, the groups that market their products, and their business contacts generally. This was an important impact since it facilitated the community’s income generation process, even during the pandemic. Second, the internet makes it possible to make video calls or participate in live online events. This means that RAMA councillors and other political leaders who support the defence of the quilombola land and rights could participate in regional and national political articulation and decision-making spaces in Brazil, such as the National Articulation of Agroecology, the National Meetings of the Quilombos, and Environment Councils.

These meetings include many discussions, advocacy and coordinations to fight for maintaining their way of life, land, rights and local economy against the backdrop of historical and structural threats faced by quilombolas communities in Brazil. These coordinations are a key factor in guaranteeing the right to land and fight invasions; fighting agribusiness and the extensive use of pesticides; engaging in collective agroecological sales to government and major buyers; exploring community-based tourism activities; and guaranteeing basic human rights for the community members. All of this has been even more challenging considering the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic in the current chaotic Brazilian political scenario. The far-right Brazilian president and his supporters bring constant threats to quilombolas and even brought racist ultra-right conservative officials to occupy government spaces that were supposed to fight racism in Brazil, such as director of the Brazilian federal foundation for the promotion of Afro-Brazilians, the Palmares Foundation.[38]

Finally, as in many countries, the pandemic led to schooling being moved online in Brazil. As classes return in a hybrid mode of online and in person, some school activities have been distributed through the internet. The connectivity helps the students to download learning materials. The pandemic also highlighted the importance of communication for personal relations and the exchange of affections in challenging times. In this scenario, the community network and internet access increased daily communications alternatives, helping people to communicate with relatives who live outside the quilombo to check on and look for each other.

Conclusion

Beyond the physical infrastructure that allows a digital network to operate, each meeting, gathering and exchange of affection and knowledge between people (the human infrastructure) was even more necessary to deploying the community network as part of this experience. It was also necessary to the parallel research. Just like the bamboo tower, our reflections would not have been possible without these links between bodies and backgrounds of diverse social groups and knowledge fields, which are crossed by historical and structural inequalities in different ways. At the same time, these are places of resistance and cultivation of other ways of living and weaving technologies.

After this experience, we added some reflections to our approach to feminist infrastructures. This field invited us to act in scenarios marked by disputes where the encounters, dialogues and multiplicity of voices will be decisive in challenging the norms. We worked through listening skills and keeping ourselves open to what can only be offered by the localised experience and specific encounters. This also helped us look at tensions and conflicts not as something that need to be stabilised but as an opportunity to open important dialogues—between ourselves and with the community members. On the other hand, it has meant seeking to build physical and digital environments that consider multiple interests and needs from an intersectional perspective that is, in fact, capable of bringing together different groups and bodies in a welcoming way when constructed collectively by different groups and bodies. This leads us to the need to address the intersectionalities of access because connectivity can otherwise become a tool that mainly benefits white cisgender men and/or reinforces patriarchal values, racism and multiple inequalities.

If community networks carry the potential to recognise, value and strengthen other ways of living and learning, it seems fitting that discussions in this area could be combined with the knowledge from other fields that are already focused on ways of breaking with imperialism and colonial legacies long before the internet. And intersectional feminism, popular education and race discussions, including whiteness, have been fundamental to our process. In another sense, research can also learn from experiences that, in practice, break with universalisation and grow from the encounter with local knowledge and social movements.

This made us understand that the wish to practise intersectionality—as both researchers building reflections and activists seeking to eliminate disparities between groups[39] —is also about looking at what is around the local experiences and not being a reproducer of structural silences of society in our research, even though this is not a linear process. This has meant looking at conflict as an opportunity to break silence or invisibility around norms and inequalities. In other words, the absence of conflict does not mean that conflicts do not exist; instead, they may not emerge at the expense of silencing or ignoring certain people to perpetuate the comfort of those who live in privileged positions. Based on our own experiences, feminist references[40] and popular education,[41] we consider contradictions and conflicts not as something that need to be ‘resolved’ or ‘stabilised.’ Rather, they have the potential to facilitate collective reflection—while keeping different places of speech in mind[42] —to build relevant community networks. And bringing them to our findings to be shared became a key element for us to build feminist research projects.

Finally, we want to highlight that among unforeseen events was one we could not have predicted: the emergence of a global pandemic and its profound negative impacts on Brazil, which was aggravated by the fact that we are going through a global health emergency under a far-right government that denies science and public health measures, violates human rights, adopts an anti-feminist stance and aggressive authoritarian inclination towards traditional communities, such as quilombolas. We do not delve into these developments in this article, but we consider it important to point out briefly how this difficult context frames our reflections when sharing the project’s findings.

The health emergency made it more difficult to plan because we did not know whether health conditions would allow our plans to be implemented. We also experienced an emotional impact from the situation as we faced and dealt with uncertainty and unknowns. In the end, we made some adjustments to be able to proceed. This period made us incorporate new questions into our reflections: how can we think of networks that are territorialised and flourish from the encounter between different people (like this project) in times when being together can be a public health risk? How will the pandemic impact the future of community networks and research? But if the pandemic prevented us from continuing the immersive and collective processes in the territory, it also stressed the need to connect the quilombo Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca community network to the internet. This was because it was a time when essential activities, such as school and access to emergency financial assistance, moved online in Brazil as a consequence of social distancing measures.

With the increased use of the internet to access public health information (such as measures to prevent Covid-19 and information on vaccines), the connection between connectivity and the right-to-know of rural populations, such as quilombola communities, has become more relevant. The pandemic was further aggravated by a deterioration in access to information by the Brazilian government. As reports by the Alianza Regional[43] point out, there is a deterioration in freedom of speech and right to information, pointing to Brazil as one of the Latin American countries where the discourse of public authorities has deteriorated, while attacks on institutions that promote access to public information grow.

Beyond the quilombolas’ right-to-know, the connection that allowed us to communicate with the community members and also hear from them in online events during the pandemic showed that connecting around fifteen families could even have an impact on the right-to-know of a greater number of people, including those from other countries who could be reading these lines right now. These nodes support the ability to insist on existing and share achievements and joys, such as when the community network made it possible for all of us to hear from them in the online live events mentioned above.

We brought the Feminist Principles of the Internet[44] to this project in our commitment to interrogating the capitalist logic that drives technology towards further privatisation, profit and corporate control. Learning from quilombolas and listening to Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca’s members and the women from RAMA was ground-breaking for known ‘alternative forms of economic power that are grounded in principles of cooperation, solidarity, commons, environmental sustainability, and openness.’[45] We saw that our experience was able to meet other feminist principles while weaving these connections, especially in terms of ‘enabling more women and queer persons to enjoy universal, acceptable, affordable, unconditional, open, meaningful and equal access to the internet’[46] and affirming the right ‘to code, design, adapt and critically and sustainably use ICTs and reclaim technology as a platform for creativity and expression, as well as to challenge the cultures of sexism and discrimination in all spaces.’[47]

We mentioned in this article our commitment to breaking hierarchies as much as possible. Possible is an important word here because, considering that unequal power relations are historical and structural, hierarchies are present in the process regardless of our commitments and wishes. In our project, thinking about whiteness made this concretely visible both for the community network and the research[48] process.

But, at the end of the day, we feel that feminist by design means exactly being able to embrace reality as it appears to us, in all its complexities, struggles and joys, while doing our best to break the silence and remain faithful to our feminist principles. This also means not hiding our own privileges and ethical responsibilities when trying to build structural change from local to global levels. The way we found to face these privileges was by opening ourselves to self and collective reflections, as well as by not being afraid to recognise that we don’t have all the answers yet but are nonetheless trying to challenge inequalities and discriminations. Considering the feminist perspectives we brought with us, our design is not a ready one-size-fits-all model. Rather, it is a work in progress that is being co-constructed, even as we write this article and engage in a dialogue with you as you read it. We felt that this action-research was made as feminist by design and was designed by many and diverse feminists.

Notes

[1] We want to give special thanks to the inhabitants of quilombo Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca, the women from RAMA, and the women involved in our work team. In addition to the authors, these are: Carla Jancz, an information security specialist who works with digital security for third sector organisations and with free technologies and autonomous networks from a feminist and holistic perspective. She is a member of MariaLab, a feminist hacker collective based in São Paulo, Brazil, that explores the intersection between gender and technology. Daiane Araujo dos Santos, a Brazilian activist in human rights and in the field of information and communication technologies, who contributes to the implementation of community networks in Brazil. She focusses on the critical appropriation of technology and its impact on people's social and community life. She lives on the periphery of the south of São Paulo (Brazil) and graduated in geography in 2018. She has worked in social movements since 2010. Glaucia Marques, an agronomist and part of the SOF (Sempreviva Feminist Organization) technical team that operates in the Vale do Ribeira region, contributing to the solidarity commercialisation, as well as agroecological and feminist technical assistance for the Agroecological Network of Women Farmers. Natália Santos Lobo, an agroecologist who is part of SOF's technical team in Vale do Ribeira. She works with the RAMA network. To finish we also want to thank all the partners and community members involved in the process and say that we are looking forward to more kitchen talks and coffees, where the transformation is being cooked!

[2] According to Daine dos Santos Araújo, the quilombos emerged as places of refuge for black people who escaped repression during the entire period of slavery in Brazil, between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. The inhabitants of these communities are called quilombolas. After the abolition of slavery, most of them preferred to continue living in the villages they formed. With the 1988 Constitution, they gained the right to own and use the land they were on. Today, Brazil has more than 15,000 quilombola communities. Read more at: https://www.genderit.org/feminist-talk/contribution-bell-hooks-and-paulo-freire-construction-community-networks.

[3] Carla Jancz, Gláucia Marques, Miriam Nobre, Renata Moreno, Rosana Miranda, Sheyla Saori, Vivian Franco, ‘Práticas feministas de transformação da economia: autonomia das mulheres e agroecologia no Vale do Ribeira’ (São Paulo: SOF, 2018). This quotation was translated by the authors. The original is available in Portuguese at http://www.sof.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Praticas-feministas-portugu%C3%AAs-web1.pdf.

[4] The National Coordination of Articulation of Black Rural Communities indicates that the existing remaining territory of the quilombola community, recognised by the Brazilian state, is a realisation of the conquests of the Afro-descendent community in Brazil, the result of the various and heroic resistances to the slave and oppressive model established in colonial Brazil, and the recognition of this historic injustice. More information available in Portuguese at: http://conaq.org.br/quem-somos/.

[5] Our group was composed of six women with multidisciplinary backgrounds. See more information in the acknowledgements at the end of this article.

[6] Different feminist authors (Haraway 1988; Ribeiro 2017; Harding 2003) have pointed out the need to question universalisation, which historically operated with the concealment and naturalisation of inequalities, even contributing to the perpetuation of Western colonialist practices in the fields of science and technology. A critical perspective regarding knowledge-building is also present in the popular education field (Freire 1996; hooks 1994). This approach encourages the development of a critical look at education and the fostering of the participation of the community as a whole to build knowledge in a way that challenges unequal power dynamics and defends people's rights, thus recognising the importance of popular and scientific knowledge. Aware that even participatory research generates and perpetuates certain types of power dynamic and imbalance, we often try to conduct our action research free from a pretension of ‘objectivity,’ ‘neutrality,’ and the reproduction of a hierarchical division between academic researchers and object-society. Even if this is not always fully achieved, we try to build our research process based on the feminist and popular education references mentioned in this article. That is to say, with a reflexive posture, promoting a constant evaluation of our methodologies, practices and ethics in each milestone of the process.

[7] Bruna Zanolli, ‘Why Do People in Communities Need Connectivity?’ Mozilla, January 9, 2020, https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/blog/why-do-people-communities-need-connectivity/.

[8] Nicola J. Bidwell and Michael Jensen, ‘Bottom-up Connectivity Strategies: Community-led Small-scale Telecommunication Infrastructure Networks in the Global South,’ APC 2019, https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/bottom-up-connectivity-strategies_0.pdf; and Association for Progressive Communications, Global Information Society Watch 2018. Available at: https://giswatch.org/sites/default/files/giswatch18_web_0.pdf.

[9] Débora Prado, ‘Community Networks and Feminist Infrastructure: Reclaiming Local Knowledge and Technologies Beyond Connectivity Solutions,’ GenderIT, November 4, 2019, https://www.genderit.org/es/node/5348.

[10] Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,’ Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): pp. 575–599; and Djamila Ribeiro, O que é Lugar de Fala? (Letramento, 2017).

[11] Tigist Shewarega Hussen, ‘“All that You Walk on to Get There”: How to Centre Feminist Ways of Knowing,’ GenderIT, August 29, 2109, https://genderit.org/editorial/all-you-walk-get-there-how-centre-feminist-ways-knowing.

[12] Bruna Zanolli, Carla Jancz, Cristiana Gonzalez, Daiane Araujo dos Santos, and Débora Prado, ‘Feminist Infrastructure and Community Networks: An Opportunity to Rethink our Connections from the Bottom up, Seeking Diversity and Autonomy,’ in Global Information Society Watch 2018: Community Networks, APC, 2018, https://www.giswatch.org/en/infrastructure/feminist-infrastructures-and-community-networks.

[13] The overrepresentation of white males in the field is not only physical and numerical; it is also historically embedded in the narratives and epistemologies of technical knowledge as colonial structures and frameworks that are imposed or naturalised in that field, thus blocking entry even to non-white cis male bodies and social groups. So, more than the numerical imbalance of white cis men occupying places of power in this field, it is important to reflect on what bodies and groups are visible and have their interests, needs and knowledge considered in places of power crossed by normative structures, such as those based on class, masculinity and whiteness.

[14] Débora Prado de Oliveira, ‘Community Networks and Invisibility Regimes of Infrastructures and Bodies,’ paper presented at LAVITS International Symposium ‘Vigilancia, Democracia y Privacidad en América Latina: Vulnerabilidades y resistencias,’ Santiago, Chile, November 29-December 1, 2017, https://lavits.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/40-Débora-Prado-de-Oliveira.pdf.

[15] Diego Vicentin, ‘Internet Governance, Infrastructure and Resistance,’ paper presented at LAVITS International Symposium,’ Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016, http://lavits.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/P8_Vicentin.pdf.

[16] Haraway 1988.

[17] Jancz, Marques, Nobre, Moreno, Miranda, Saori, and Franco 2018.

[18] RAMA is composed of the following groups: As Margaridas (Bairro Indaiatuba), Rosas do Vale (Bairro Córrego da Onça e do Franco), As Perobas (Quilombo Terra Seca), Mulheres do Quilombo Ribeirão Grande, Mulheres do Quilombo Cedro, Mulheres do Bairro Rio Vermelho, Grupo Esperança (Bairro Bela Vista), Mulheres do Conchas. The women's group called Perobas is the RAMA subgroup that brings together women from the Terra Seca quilombo. They are quilombola agroecological farmers who gather together to organise the women of the neighbourhood to join mixed organisations (in cooperatives and associations, for example). They also perform their own actions for the group of women in the neighbourhood and get together to market their products to responsible consumers in the cities of Registro and São Paulo. More information is available in Portuguese at: https://www.sof.org.br/2020-comecou-com-mais-um-encontro-de-redes-de-comercializacao-solidaria-em-barra-do-turvo/.

[19] This previous activity by SOF and the relationship of trust they built with the networks of local women farmers was fundamental to our action-research project. This is principally because it was SOF, in collaboration with RAMA and MariaLab feminist organisation member Carla Jancz, that began to imagine a community network in the Vale do Ribeira region back in 2017. SOF wanted to realise communication autonomy in the territory: ‘In the Vale do Ribeira, we took the first steps to seeking communication autonomy with the realisation of the project’s information technology workshop, “Capacity Building and Sharing Experiences for an Inclusive Economy,” with the support of the British Council’s Newton Fund. In this initial visit, a network technician, Carla Jancz, made a first general analysis of the territory and talked to the women about the possibility of installing an autonomous network to distribute internet on site in the future’ (Jancz, Marques, Nobre, Moreno, Miranda, Saori, and Franco 2018).

[20] For more on reflexivity, please see Hussen 2019.

[21] The option for an immersion for longer periods and the realisation of more visits to quilombo Ribeirão Grande/Terra Seca arose from a conversation with a local leader, Nilce de Pontes Pereira dos Santos, the founder of the Association of Quilombos Remnants of Riberão Grande and neighbourhoods of the city of Barra do Turvo and a representative of the National Coordination of Quilombola Communities (CONAQ) within the National Agroecological Articulation. In a preparatory conversation for our first trip to Quilombo, Nilce expressed enthusiasm for the idea of the community network in the region, but also expressed some concerns about the process. These concerns were: 1) she complained about some researchers from Brazilian universities who went to the territory, collected data and never returned; 2) the appropriation of local knowledge by people associated with research institutions; 3) issues with different temporalities between the field and the city. More specifically, with the lack of time researchers tend to stay in the territory and establish collaboration in the field, where the relationship with time is different to that of large cities; and 4) security issues in the use of the new network, especially in relation to young people using digital networks.

[22] For reasons of space in this article, we will not describe in detail the methodology of each immersion performed. However, this is a point that can still be better explored and shared in future developments of this project.

[23] During the last trip, we had to adapt our methodology in light of the pandemic. Instead of collective conversations and reflections from five previous visits, we carried out semi-structured interviews with people who participated in the process, aiming to gather elements for a joint evaluation of the trajectory.

[24] Our initial idea was to share our research reflections with the community at the end of the process of installing the network and discuss issues like these dynamically, by following the model of immersions we had performed. However, with the Covid-19 pandemic, completion of the installation of the community network was delayed and, to safeguard all those involved, we had to cancel the collective meetings.

[25] Bidwell and Jenson 2019.

[26] See Ribeiro 2017; and Patricia Hill Collins, ‘Se perdeu na tradução? Feminismo negro, interseccionalidade e política emancipatória,’ Parágrafo 5, no. 1 (2017). Available at: http://revistaseletronicas.fiamfaam.br/index.php/recicofi/article/view/559.

[27] Read more about PetraLab here: https://www.pretalab.com/en/home.

[28] Lia Vainer Schucman, ‘Yes, We Are Racists: A Psychosocial Study of Whiteness in São Paulo,’ Psicol. Soc. 26, no.1 (2014): pp.83–94, http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822014000100010.

[29] Schucman 2014.

[30] Laura Forlano, ‘Infrastructuring as Critical Feminist Technoscientific Practice,’ Spheres: Journal for Digital Culture 3 (2017), http://spheres-journal.org/infrastructuring-as-critical-feminist-technoscientific-practice/; Sophie Toupin and Alexandra Hache, ‘Feminist Autonomous Infrastructures,’ in Global Information Society Watch 2015: Sexual Rights and the Internet (APC and Hivos, 2015), https://giswatch.org/sites/default/files/gw2015-full-report.pdf; Jancz, Marques, Nobre, Moreno, Miranda, Saori, and Franco 2018.

[31] Prado 2019.

[32] Read more about LibreMesh here: https://libremesh.org/.

[33] Read more about Raspberry Pi here: https://www.raspberrypi.org/.

[34] Read more about Pirate Box here: https://piratebox.cc/.

[35] Read more about Fuxico (in Portuguese) here.

[36] This assumption is a point that can be further explored in future research on the impacts of the community network in the territory. This has not yet been possible at this stage of the research project due to the need for a time window.

[37] Read more here and here.

[38] Jane Coaston, ‘The Intersectionality Wars,’ Vox May 28, 2019, https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/5/20/18542843/intersectionality-conservatism-law-race-gender-discrimination.

[39] Our main references come from feminist studies in science and technology (Haraway 1988; Harding 1998) and intersectional feminism (Collins 2017; Crenshaw 2002; Piscitelli 2009).

[40] bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (Routledge: New York, 1994); Paulo Freire, Pedagogia da Autonomia - Saberes Necessárias à Prática Educativa (São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1996).

[41] In dialogue with the theoretical legacy of black women and bringing the perspective of the place of speech, the Brazilian philosopher Djamila Ribeiro emphasises the importance of locating components that are understood as a universal condition. She highlights, for example, discussions around race and racism, which cannot be done solely by black people.

[42] The report is available here (in Spanish): https://www.alianzaregional.net/wp-content/uploads/Institutional-Policies-Alianza-Regional2.pdf

[43] The Feminist Principles of the Internet are a series of statements that offer a gendered and sexual rights lens on critical internet-related rights. More information is available at: https://feministinternet.org/en/about.

[44] https://feministinternet.org/en/principle/economy

[45] https://feministinternet.org/en/principle/access

[46] https://feministinternet.org/en/principle/usage

[47] In the field of feminist research, read more reflections in Hussen 2019.

This report is part of the Feminist by Design journal, published by APRIA (ArtEZ Platform for Research Interventions of the Arts). The journal showcases research journeys, findings and feminist intentions, bringing together a diverse group of researchers from around the world who were part of the Feminist Internet Research Network (FIRN).